Nancy Sánchez Tarragó

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5114-6072

Universidade Federal de Rio Grande do Norte

Information Science Department

1. Introduction

Scientific journals are a fundamental part of the scientific communication system, along with other vehicles such as books, event papers, preprints, data, and software, among others. The founding in 1665 of the first academic journals (Journal des Sçavans and Philosophical Transactions) started an entire tradition that combines the functions of registration, dissemination, certification, and archiving of knowledge, which remains unchanged in its essence to this day.(1)

From Europe, scientific journals, with their functions and traditions, expanded to different parts of the world, assuming specific characteristics. In several countries in Europe and in the United States, for example, since the 1960s, commercial scientific journals predominate, many of them edited by high-profit oligopolies.(2) These companies have departments and employees who professionally perform most of the functions and procedures that make up editorial management and production. Commercial journals also predominate in bibliographic and citation indexes (such as Web of Science and Scopus) that guide the quality criteria of journals, mark their reputation and, with it, that of the researchers who use these channels. Additionally, journals have gone from charging for reading to charging for publishing, creating new inequities (3).

In contrast, the Latin American region has not developed a commercial circuit for scientific journals, which continue to be published mainly by universities, subsidized by public funds, and largely supported by the voluntary efforts of professors, researchers, and other officials of those institutions. The main objectives that guide these journals, therefore, are not economic, but associated with an understanding of knowledge as a common good. The journals of this region also moved almost naturally towards open access (from printed, they became electronic, placing their content freely on the Internet). Latin America was a pioneer in developing initiatives aimed at achieving, cooperatively, an expanded dissemination of scientific production in the region, in order to achieve greater visibility and accessibility, as well as a reduction of social, economic, and epistemic gaps and inequities, within the region and with respect to other regions. (4,5)

LILACS, SciELO, Redalyc, CLACSO, and AmeliCA, among others, are initiatives created to also promote higher quality in the publication of journals, as well as alternative science measurements to those imposed by developed countries, seeking to get out of the vicious circle in that lower quality and accessibility implies less visibility, less use, less recognition and, therefore, less possibility of attracting quality articles, financing and, once again, achieving recognition and academic and social impact. In the end, we want to contribute to national, regional, and international science and for that it is necessary that the journals be read and valued.

As part of the efforts promoted by LILACS (Latin American Literature in Health Sciences) to raise the quality of the editorial processes of scientific journals in Latin America and the Caribbean, within the framework of the webinar “Best practices in LILACS editorial processes 2020” I gave a lecture (6) of which the present chapter is an expanded version. Its objective is to characterize the main stages that constitute the scientific and editorial management of journals, their participants, and functions, trying to show best practices in the organization and management of editorial processes.

2. The contemporary scientific journal: functions and expectations

What is a scientific journal? According to the ISO 8:2019 (7), a journal is a serial publication, which is repeated at regular intervals of time, in printed or electronic format, dedicated to disseminating original research and other types of contributions about the developments of a discipline, subdiscipline, field of study or profession, with the purpose of being published indefinitely, whatever its periodicity.

Its role as a channel for scientific communication is becoming increasingly important in most areas of knowledge. During the last 20 years various studies have investigated the needs and motivations of researchers in relation to scientific journals. These vary according to whether they are authors or readers, since the degree of overlap between these two roles varies from discipline to discipline, influenced by the size of the discipline. For example, in a relatively small field such as Theoretical Physics, a 100% overlap is estimated, however, in fields such as medicine or nursing, readers will be much more numerous than authors. (8)

Research shows that contemporary authors publish primarily to spread their ideas, and then to build a reputation, promote their career, and get funding. (1,8) Reputation building is associated with the registration and public recognition of a contribution through its publication in journals perceived as prestigious and “high impact”. In the last 30 years, there has been a growing interest from national science evaluation and financing systems to measure the performance of researchers through quantitative indicators of the production of articles and citations, leading to distortions such as “publish or perish” and the abuse of the impact factor indicator, developed by Eugene Garfield for the bibliographic indices found in Web of Science, which has become a preferred indicator of these evaluation systems to estimate the quality and impact of journals, and indirectly, of the authors who publish in them. (9)

The main characteristics that authors take into account when selecting the journal in which to publish are quality and reputation, relevance, quality of peer review, and speed of publication. (8) In addition to an agile, fair, and well-argued evaluation and rapid publication, the authors expect diligent, careful, and faithful editing to the original. (10) Recent studies suggest that open access status is also emerging as an important secondary factor, especially if it does not involve payments for article processing (APC-article processing charge). (8)

For readers, on the other hand, the four traditional functions of scientific journals (registration, dissemination, certification, and archiving of knowledge) are essential. The registry allows them to evaluate who the authors are in a scientific domain; certification allows them to select information according to its quality and reliability; the dissemination function allows journals to be classified according to their specialty, focus, and sections, while the archiving of articles allows for the existence of a repository of knowledge that can be accessed and consulted over time (1). Also, the authors hope to find current and relevant topics in well-written and well-presented texts (10). In more recent years, within the framework of movements such as those of open access and open science, not only have access to texts, but also to complementary materials such as data sets, multimedia resources, among others, are also established as expectations. Institutions and funding agencies to which the authors/readers are linked are also interested in journals performing their duties properly.

To meet these expectations of authors, readers, and institutions, two actors are fundamental in the scientific communication supply chain: publishers, who are responsible for managing the quality control, production, distribution, and long-term preservation of the content, and librarians, in principle, responsible for managing content access and navigation, but who currently share other responsibilities with publishers such as standardization, indexing, publication, dissemination, and preservation of content. Naturally, these two actors work together and collaboratively with many other actors during different stages of the editorial processes.

In recent decades, among the most significant transformations that have been observed in relation to scientific journals are the transition from printed to electronic format, and the prominence of open science movements, mainly oriented towards the publication of open access journals and the deposit of articles, preprints and data in open access repositories. This occurs in a context of marked commercialization of intellectual products, the consolidation of editorial oligopolies, and an increasing emphasis on systems for evaluating researchers that measure their performance by publication in journals of quality. This quality has often been almost exclusively associated with the indexing of the journal in indexes or databases such as Web of Science and Scopus and obtaining specific indicators, e.g., the impact factor, despite criticisms and limitations of its use. (11)

However, there are certain consensus on what should govern the quality of a journal in order for it to fulfill its functions and satisfy the expectations of the scientific community and society in general: quality of the editorial staff, integrity of the article evaluation process, adoption of standards, regularity in the periodicity, use of modern management tools that contribute to more agile, efficient, and transparent processes, as well as metadata and full-text files in formats that favor interoperability and wide dissemination.

In the next sections we will see how editors, librarians, and other members of the editorial team manage and participate in editorial processes to guarantee the quality and relevance of scientific journals.

3. Management of scientific journals and the editorial process

The management of a scientific journal involves two large areas: scientific management and editorial production management. The first includes scientific certification processes based on the evaluation of manuscripts and the selection and dissemination of credible and valid scientific results. The second stage refers to the editorial production processes, administrative and financial management, marketing and dissemination, among others. (12) In this chapter I will not address administrative and financial management.

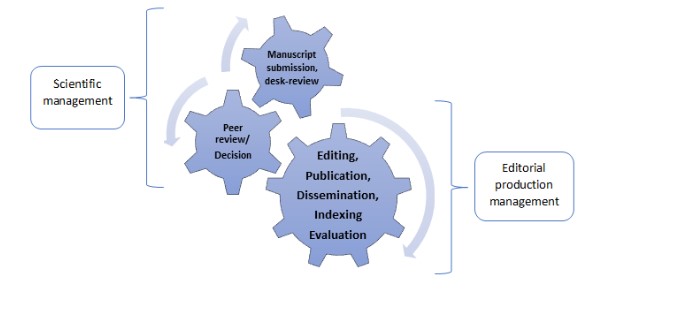

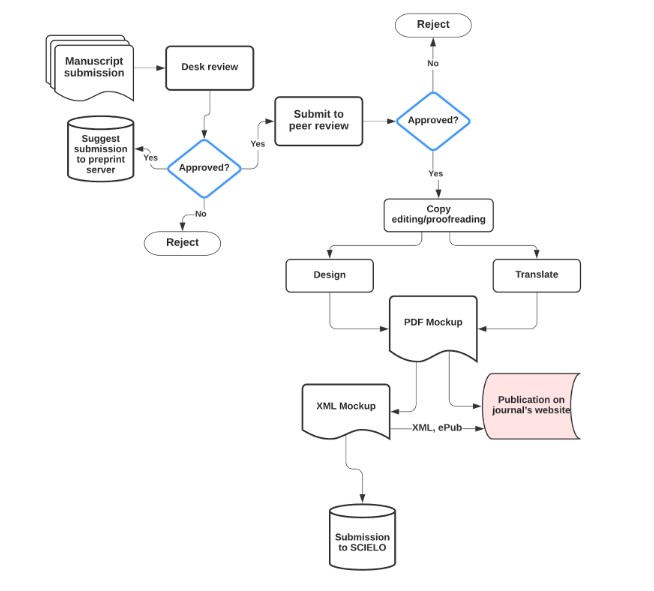

The editorial process is the set of specialized procedures and activities organized with the objective of producing and distributing a publication (Figure 1). It unfolds in a sequence of stages that are not necessarily linear, because sometimes, to advance towards the final objective (publication and distribution), we will have to go back to some previous stage or develop stages simultaneously.

The best metaphor to illustrate an editorial process is that of a gear made up of various pieces: the members of the editorial team, with their specific skills and tasks, on whose quality work the correct functioning of the entire process and the product’s final quality depend, and the different stages and procedures that they develop.

Figure 1. General stages in the editorial process of a scientific journal

3.1 Who are the editorial process participants?

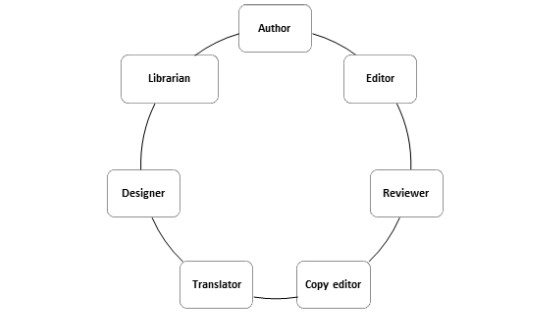

An editorial process is a collaborative effort, where various actors participate in different roles (Figure 2). This teamwork ranges from the author; to the editor, considered a generic figure that can include various nomenclatures and roles (managing editor, section editor, associate editor), to the members of the editorial committee (policy committee, scientific committee). It also includes the copy editor, designer, translator, and librarian, among others.

Figure 2. Editorial processes participants

Obviously, the separation of these roles and responsibilities will depend on the administrative and organizational structure of the journal, for example, if it is included within a publishing house that publishes several journals, or if it is a single journal published by an institution, a department, or an individual. In the first case, it is very likely that there are many of these separate functions, performed by different people. In the second case, such as a journal edited by a university department, it is quite common for the same person to accumulate several roles. We are going to briefly see what the roles of each of these actors are in the editorial process.

Author

The author has an essential role in the editorial process. Even though the work of the journal editors, reviewers, and other members is essential to guarantee the quality of the articles and the journal, the initial quality of the “raw material” is crucial. Therefore, it is extremely important that authors take responsibility for the formal quality, and that of the content, of their manuscripts. Vázquez (13), in a conference marked by the webinar “Best practices in LILACS editorial processes 2019”, highlights that a good article must present relevant, interesting, up-to-date, novel, rigorous content from a methodological point of view, but it must also be well written, that is, it must be clear, concise, correctly use scientific language and the rules of the language in which it is written. These qualities give the manuscript credibility and increase its chances of being accepted, published, and having a scientific and social impact. The author must also be an active participant in the editorial process, maintaining an agile and respectful communication with the editor with whom he must interact in various phases of the editorial process.

Editor and advisory boards

The figure of the editor, as mentioned earlier, can include various functions, some more managerial, others more academic. It is also possible that these functions be shared between several people. To see a more detailed nomenclature of editors and their functions I suggest checking Trzesniak (14). It is necessary to bear in mind that in many Latin American countries there is also the figure of the journal director, who in some cases could be equivalent to managing editor. If we consider the functions of the managing or executive editors in many scientific journals from Latin American countries, it can be said that the editor is responsible for:

- Execute the editorial policy

- Control the quality dimensions of the journal

- Ethical control of all processes

- Management of the editorial process

- Request or order items when needed

- Contact and send manuscripts to the reviewers

- Assign tasks to Section Editors

- Articulation with members of the editorial board (copy editor, designer, librarian)

- Final decision on the articles’ publication

- Create the journal issues, schedule submissions for publication, organize the summary, and publish the issue as part of the publishing process

- Organize and supervise the indexing, dissemination, and evaluation processes of the journal

In a general sense, the editor (who is often a professional or researcher in a specific discipline) must be able to acquire a broad and flexible vision of the scientific domain that is within the mission and scope of the journal: its methods, procedures, concepts, expressions, interdisciplinary relationships, but also research areas, the most influential or most relevant authors, institutions, or research groups within that area. This knowledge will help the editor to “filter” the works received by the journal, identifying their limitations and potential, but also to be able to identify possible reviewers, section editors, and authors who can contribute to the journal.

The managing editor is also in charge of articulating that the editorial process works like a gear, according to the metaphor we used before and for that they must ensure consistency, uniformity, and standardization in editorial practices and processes. Does that mean that the editing of all the articles in a journal will happen in an identical way? Of course not. It may happen that some articles force us to make different decisions adjusted to the circumstance in question; however, everything must occur within a framework of consistent and coherent practices and processes. To establish this framework, journals rely on editorial policies and the establishment of standards and guidelines for the editorial team and for authors. Editorial policies guide, for example, the publication’s mission, its audience, its editorial profile (topics, types of articles), the forms of access to the contents (open access, via subscription), the criteria and manners of evaluation of the manuscripts. They also establish the aspects related to the intellectual property of the articles, the licenses for use, as well as the guidelines that the authors must comply with when submitting the manuscripts. More information on editorial policies can be found at the Trzesniak conference in the 2020 edition of the webinar “Best practices in editorial processes”. (15)

It is necessary to bear in mind, as Paula highlights in a conference held in the LILACS 2019 “Best Editorial Practices” webinar (16), that consistency and standardization must be transversal to all editorial processes. Standardization allows, for example, for maintaining consistency in the structure of scientific articles; in the format of authority data (authors, institutions, degrees, etc.); in the use of standards for identifying authors, journals, and articles (such as ORCID-Open Researcher and Contributor ID, ISSN-International Standard Serial Number y DOI-Digital Object Identifier, respectively); in the style of bibliographic references; and in the format of abstracts, calls, and footnotes of tables and illustrations, among other elements. These qualities will not only reflect and reinforce the credibility, transparency, and integrity of the journal and published research, but will also allow articles to be indexed in databases and directories, thus increasing the possibility of retrieval and access.

It is important to highlight that the work of the editor of a scientific journal must be supported by one or more advisory committees, whose members are representatives of various institutions that support the journal. Some journals have at least two advisory bodies: an editorial policy committee, responsible for preparing and approving editorial policies, and a scientific council, which collaborates with the editor in the selection of articles to be published, the discussion of peer-review, and the creation of thematic issues, among other attributions. (14) (17)

Reviewer

The reviewers are those selected and invited by an editor to review a manuscript. They do not have a permanent link with the journal, nor are they necessarily members of the advisory councils. They are people with a specific domain on a topic at a certain time. Usually, the editor selects a reviewer because they research and publish on the journal’s topics of interest. They may be a professional in the field, even if they do not have an academic title; or they may even be a doctoral student. The general rule of thumb is that they have proven competencies to perform the review. Some studies even show that junior researchers tend to provide more detailed and comprehensive reviews compared to senior researchers. (18)

Copy editor

The function of the copy editor is to edit the manuscripts to improve grammar and clarity, as well as the adherence to the bibliographic and textual style of the journal. This style should be materialized in a manual or style guide to guarantee the consistency of these processes over time, as well as to correspond with the guidelines given to the authors. Some journals have an editor or section editor who performs this role.

Designer

Graphic design enhances communication. It is what organizes perception, what gives a common thread to attention and reading. Letters, numbers, colors, and graphic and textual elements are the responsibility of the designer/layout designer/typesetter who organizes and distributes these elements on the page and prepares, reviews, and adjusts the figures that make up the article, in accordance with the journal’s policies. Currently, with the predominance of electronic and multimedia journals, this function can also include the transformation of corrected versions of manuscripts in HTML, PDF, XML, and ePUB formats, among others. In some journals, it is also a role that is performed by an editor or other professional who has developed skills in this area.

Translator

The current quality criteria for scientific journals recommend that the title, abstract, and keywords of the articles be included in at least two languages (the original of the article and English). For Latin America, where Spanish and Portuguese are mainly spoken, a language policy that includes these two languages, plus English, is important as a mechanism for greater inclusion. Although it is generally the authors who must provide the translated versions, some publishing houses have a professional translator to prepare or revise the translations or contract this service to third parties.

And what is the role of the librarian in the editorial process?

The importance of the action of librarians in scientific communication processes has grown steadily in the last 25 years, in parallel with the transformations of the publishing industry: the emergence of digital technologies in the publication of journals, the movement of open access to information (with the rise of repositories and open access journal portals), the growing relevance of metadata and interoperability, of digital preservation, and of indexing in databases. Additionally, bibliometric and altmetric indicators for evaluating the quality and visibility of journals and new forms of dissemination on social networks and digital marketing also have a growing importance in scientific communication and editorial processes. All these areas have required a reordering of the editorial teams, and even of the missions of the libraries and their professionals.

An interesting aspect is that, with the increasing use of digital technologies in publishing processes, these processes are no longer exclusive to classical publishing houses. Other types of organizations, including libraries, include these functions as part of their strategy to promote library products and services, as well as to support the creation, dissemination, and curation of scientific, artistic, and educational work. (19–21) This implies the development and expansion of various competencies that cover, not only more traditional knowledge and skills in the library field, such as standardization and work with metadata, but also knowledge about scientific communication and new models of publication, mastery of digital technologies, editorial management, bibliometric studies, and marketing, among others. Communication skills, teamwork, ethics, creativity, and leadership are also important. (22–26)

Some Latin American research has investigated the specific roles and tasks related to the publishing of scientific journals that librarians carry out in editorial teams. Table 1 is presented from some of them, although it does not intend to be an exhaustive list. Note that it includes an Executive Editor role, to emphasize that the librarian can also occupy this responsibility, although many of the specific functions indicated in the Management box overlap within the roles of this actor.

Table 1. Functions that librarians can perform in the field of journal editing

| Management | |

| Executive editor

Development of editorial projects Development of editorial policies Development of open access, open data policies Assistance to authors and reviewers |

Editorial flow management

ISSN management Advice on copyright, licenses, and plagiarism Management of editing platforms (e.g., OJS) Coordination of journal portals Bibliometric, altmetric studies/journal evaluation |

| Editing, standardization, and layout | Promotion and visibility |

| Copy-editing and revision of texts

Correction and standardization of citations and references, figures, and tables Application of anti-plagiarism software Layout/creation of PDF and other versions Web and image design DOI (Digital Object Identifier) designation Markup articles to be entered into databases |

Creation and selection of content for social media networks

Management of social media profiles Indexing in databases and institutional repositories |

Source: prepared from Díaz Álvarez and Sánchez-Tarragó(24), Gilmet (22), Rozemblum and Banzato (27), and Santana and Francelin (28).

It is important to reinforce that publication in scientific journals constitutes one of the fundamental indicators of scientific activity and that its quality is measured, among other aspects, through its indexing in databases, bibliographic repertoires, and citation indexes. Therefore, the alliance between editors and librarians is becoming essential to ensure that scientific journals comply with the evaluation indicators established not only by national science evaluation systems, but also regional and international systems such as LILACS, Latindex, RedALyC, SciELO, Web of Science, Scopus, the Directory of Open Access Journals (DOAJ), among many others, which promote visibility and access to the journal. The professional training of librarians provides the knowledge and the long tradition in the field of creation and management of bibliographic databases and repertoires (27), which currently extends to the creation and management of repositories and journal portals.

Ultimately, the participation of the librarian will be determined, on the one hand, by the opportunities that open in the editorial teams, based on an expanded vision of the editors and the editorial team about the new roles and the interdisciplinarity of the editorial work; and, in many cases, by the proactive attitude of the librarian and information institutions, which must be ready to take on new challenges and develop new skills.

3.2 Stages of the editorial process

The functions that journals perform have remained almost unchanged in the last 200 years, however, how to perform those roles has undergone enormous transformations since the beginning of the 21st century. One of the major transformations has come from the hand of electronic journal management systems (EJMS), which are web platforms that allow for managing the entire editorial process, from the sending and receiving of originals, the evaluation of manuscripts, to their publication and dissemination in multiple formats. They allow for the creation of records of all the operations carried out during the editorial process and the elaboration of statistical reports.

Some of the most used are listed here:

- Open Journal System (Public Knowledge Project-University of British Columbia)

- ScholarOne Manuscript (Clarivate Analytic)

- BePress (University of Berkeley-Elsevier)

- Editorial Manager (Aries Systems)

- EVISE (Elsevier)

- Editorial Express (Techno Luddites)

- BenchPress (Highwire)

- Manuscript Manager (Akron ApS)

- GN Papers (GN1)

These systems encompass each of the stages of the editorial process, so that each user can register on the platform and create an account, according to their role in this process (reader, author, reviewer, managing editor, section editor, proofreader, etc.). From these roles the user will have certain levels of access and permissions. On the platform, the editorial process is broken down into a series of stages, some are sequential and mandatory, so that the software does not allow progress if one of the required steps has not been taken in an orderly fashion. (29)

Current experience shows that the adoption of EJMS has many advantages for the professionalization of editorial work, maximizing management efficiency and transparency of all processes. Among the advantages are the agility in the management of originals and publication, by allowing to register and control the response times both for the peer-review and for the rest of the processes, including, allowing to send automatic notices to alert of delays; an improvement in the fulfillment of standardization criteria by means of a checklist that must be fulfilled by the authors in order to send their manuscripts; increased visibility of articles, thanks to the adoption of the OAIPMH (Open Archive Initiative – Protocol for Metadata Harvesting) metadata protocol, which allows the metadata registered by the authors to be automatically harvested by different databases and search engines. In addition, these systems generate persistent identifiers, such as DOIs, and allow the export of their contents according to different standards, based on XML. Last but not least, journal management systems include utilities to generate reports and statistics that help to obtain an accurate description of the status of the publication, among them, visit counters that allow identifying the most visited articles, in addition to the origin of visitors. (29)

Below, I succinctly explain each of the stages of the editorial process.

Manuscript submission, acceptance, and evaluation

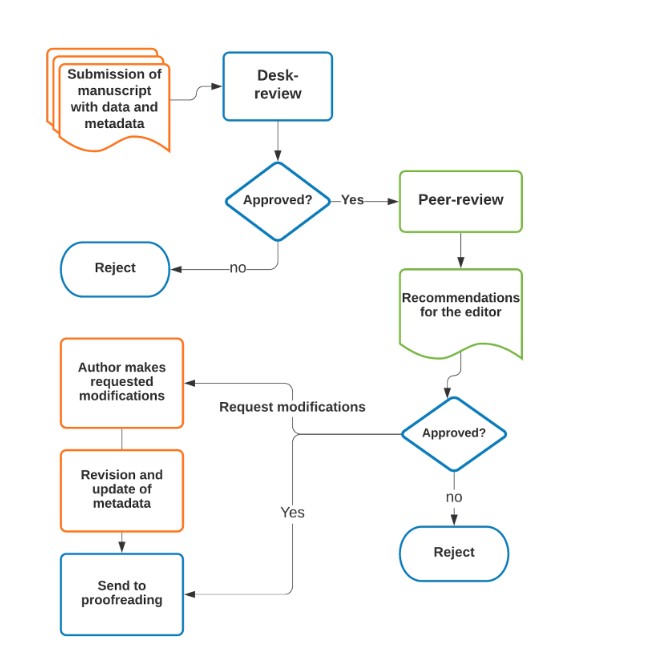

The editorial process begins with the submission of the manuscript by the author (Figure 3). As I indicated before, it is convenient that the manuscript be sent using an electronic journal management system. Also, it is important that the possibility of submissions to the journal is always open. In this way the manuscripts will go through their different stages, simultaneously. A journal that temporarily suspends the receipt of new manuscripts will probably be losing potential submissions, as authors will seek other journals to publish.

Figure 3. Stages of the editorial process: manuscript submission and evaluation

Electronic journal management systems typically allow authors to submit, in addition to the main file, supplementary files (data sets, images), as well as metadata describing the manuscript and its authors. For example, for each author, first and last names, institutional affiliation, ORCID, and email must be indicated, and for the manuscript, title, abstract, and keywords. Depending on the type of EJMS, its version and configuration, it may be necessary to include the manuscript metadata in several languages, as well as include bibliographic references. The availability and quality of this metadata is very important so that it is automatically harvested by service providers such as databases and search engines, maximizing the visibility of and access to the articles.

It is also important to bear in mind that the EJMS usually uses the information available in the metadata fields to display the “cover” of the articles on the main page of the journal. If the author did not send the names of all the co-authors, for example, and that lack was not corrected during the editorial process, the article could be published without the names of those co-authors, or as has sometimes happened, the article is published with the names of the authors, but only the name of the main author appears on the “cover” of the journal’s website, creating inconsistency in such important information.

Desk-review

Once the editor receives the manuscript, they proceed to carry out a preliminary evaluation, before deciding to send it to external reviewers (some journals call this stage desk-review, others triage or screening). This preliminary review is the first quality filter. We know that the number of manuscripts submitted for publication is increasing. This places stresses on the editorial processes and specifically on the peer review process. Most reviewers are active professionals, who work on their own research, in teaching, in management positions, or in other professional activities with which they share, generally on a voluntary basis and without remuneration or rewards, the peer review work. Their time and efforts are therefore scarce and precious.

Considering that it is a very important stage, but there is less systematized information about it, I am going to dedicate more space to it. What is observed at this stage? The criteria can be grouped into five blocks (30–32):

- Adherence of the proposed article to the scope or editorial scope and mission of the journal. If the article does not correspond to the editorial scope and mission, there are legitimate reasons to be rejected. However, this reinforces the importance of making this information explicit on the journal’s website, reinforcing that it will be a criterion for rejection.

- Integrity of the research. Manuscript must comply with ethical guidelines for scientific publication. In this sense, I recommend seeing the conference “Ethics in scientific publication” (33) and the guide of the Committee on Publication Ethics-COPE. (34) Many journals runs all manuscripts through a computerized plagiarism detection software.

- Theoretical contribution and scientific value. These are fundamental aspects within the preliminary evaluation: novelty and originality, as well as theoretical or methodological contribution, must be requirements that, if not fulfilled, would disqualify the manuscript.

- Methods. The objective description of the methodology and didactic presentation of the empirical data is considered as an indication of the authors’ zeal in the completion of the manuscripts. (30) Also, concerning the explicit existence of research objectives or questions and their correspondence with the selected methods. Journals can define, for example, whether they will accept analytical papers, rather than merely descriptive ones.

- Writing, organization, and structure of the text. According to the scope and mission of the journal and its subject area, there is a “canonical” structure for the organization of scientific texts. This gives clarity, coherence, and logical consistency to the exposition, leading to a better understanding of the text and more credibility. The clarity and conciseness of the language also play an important role. The journals establish standards of style and instructions for authors with requirements on these aspects. In this desk-review, the editor is also usually attentive to whether or not the author adheres to the style guidelines and submission requirements of the journal; for example, inclusion of elements such as keywords, abstract, source or title of tables and figures; adherence to style guidelines for citations and bibliographic references; and observance of non-identification requirements of the texts for compliance with blind review, if this is the review model adopted by the journal.

However, it is necessary to emphasize that criteria unrelated to scientific and ethical issues, such as those related to the journal’s style guidelines, would deserve a resubmission request rather than a rejection. Additionally, it is necessary to be vigilant against possible biases and conflicts of interest of the editors that could contaminate the fairness of the preliminary evaluations, determining the rejection or acceptance of manuscripts for spurious reasons. (32)

Finally, two aspects should be highlighted in this process: the period that the author waits to receive a decision on their manuscript and the justifications offered for its rejection. According to the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE), “if a journal does not intend to continue with a manuscript, the editors should endeavor to reject the manuscript as soon as possible to allow the authors to send it to a different journal” (35). However, not specifying a timeframe can cause confusion. Teixeira et al. (32) recommend that this timeframe not exceed one week and that this information be made explicit by the journal in its “Instructions for authors” section.

Regarding the justifications for rejection, Teixeira et al. (32) recommend that the rejection letter not be a generic letter, but rather a list of reasons specific to the manuscript in question. Although obviously this can increase the work of the editors, especially for those journals with a higher volume of submissions, the sense is that the criticism is beneficial for both the author and the editor, since this approach can increase the quality of the manuscripts that will be resubmitted (for the same journal or for others), because it allows authors to reflect on the criticized aspects and improve based on these criteria.

Peer review

Ultimately, improving received manuscripts and transforming them into good articles is the goal of most editors. Therefore, those manuscripts that passed the desk-review go to the peer review stage. Peer review is the critical evaluation by specialists of the manuscripts submitted to the journal and currently has different forms ranging from the traditional “double blind”, where neither reviewers nor authors know each other’s identity, to open review, with various variants (36), in which the identities are revealed and the content of the reviews is also published. For most bibliographic databases, citation indexes, and journal directories, the existence of the peer review process and the formal specification of the procedure in question constitutes a quality criterion for admission of the journal, including the disclosure of the main dates related to the process (for example, date of receipt of the manuscript, representation by the author, and approval). As an example, see LILACS guidelines (37) and the recommendations of the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors (ICMJE) (35).

Peer review is a process that is not without its limitations and criticisms, but it should be understood not only as quality control, but as “a distributed effort to recognize and increase the value of manuscripts”. (38) Therefore, it must be inherently constructive, in a safe environment of connection and cooperation (direct and indirect) between authors, reviewers, and editors. In other words, it is an evaluation that highlights the strengths of the research and makes recommendations to strengthen its weaknesses, with a focus on methodological aspects. (39)

It is essential to establish guidelines for reviewers (within editorial policies), defining the aspects to be observed during the review, which also allows for, within the inevitable subjectivity of an evaluation, a certain uniformity and consistency in the process. Journals generally maintain databases of regular reviewers, with identifying data, including review interests, but sometimes it is necessary to search databases or professional directories to identify new reviewers. Other aspects related to the management of peer review, the assignment of reviewers, and the role of reviewers, authors, and editors in the process can be explored in more detail in the series of articles of Rodríguez (39,40).

Reviewers are generally asked to make recommendations to the editor to help decide about the manuscript; this decision is usually in the range of rejecting, requesting modifications, or approving. Whatever the decision, the editor must communicate it to the author immediately. Electronic journal systems such as some versions of Open Journal System allow the editor to send the reviewer a blind copy of the communication that is sent to the author. Personally, I consider it an interesting option to acknowledge the reviewer’s performance, even when the decision that the editor makes does not necessarily agree with the recommendation of all the reviewers participating in the evaluation of the article. It is worth noting that the reviewers’ recommendations are optional and serve as a guide and orientation for the editor, who has the last word.

It is common that more than one round of review and interaction between authors, reviewers, and editors can take place, but when the manuscript is finally approved, we can move on to the next stage. Here it is necessary to draw attention to the need to update the metadata of the manuscript in the journal management platform. Once the author sends the final approved version, we must verify that possible changes made in the title, abstract, keywords, and bibliographic references, are reflected in the metadata to guarantee its quality.

Finally, it is highly recommended to send a thank you message to each reviewer who completed their task. ERMS usually have mechanisms to automate and personalize these messages. Many journals also list the names of the participating reviewers at the end of each published volume.

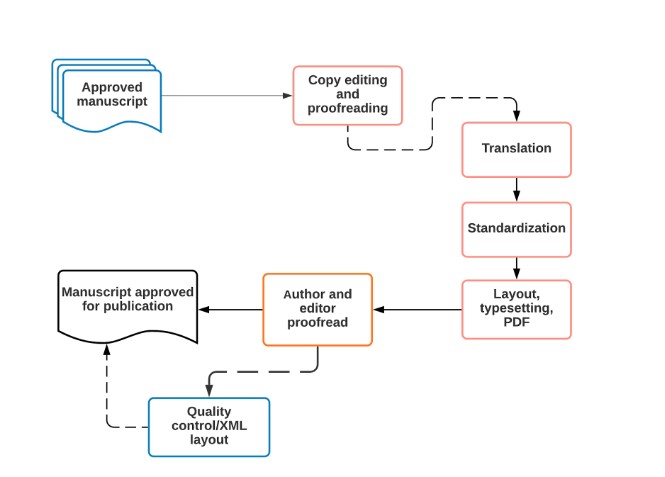

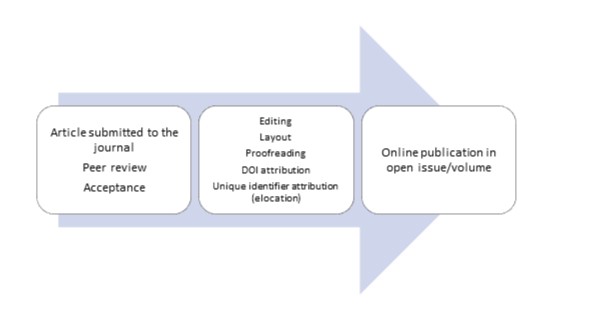

Editorial production

Once the manuscript is approved after one or more rounds of peer review, it goes to the editorial production stage. This stage includes several processes such as copy editing and proofreading, standardization, translation, design, layout, and the production of different formats of the article (for example, PDF, XML, ePub) (Figure 4).

These processes also require guidelines and standards for consistency. For example, the journal may have a style guide to aid the copy editing/ proofreading of texts, including the style guide for bibliographic references. There may also be rules for the writing of names, institutional affiliations, for the elaboration of figures and the treatment of other graphic elements. Furthermore, the flow of the manuscript between the different processes may vary according to the journal and this should be standardized. Regarding standardization aspects, I suggest consulting Paula’s presentation (16).

Figure 4. Stages of the editorial process: editorial production

The layout (also called mockup) can be helped using templates where the space, the format of columns and paragraphs, the graphic elements such as logos and headers are organized beforehand, to speed up the production of articles and guarantee consistency between the articles that make up the journal. Currently these layouts can be made in different programs and formats, including PDF and XML.

Once the manuscript is diagrammed, proofreading or a galley proof is necessary. This name comes from the time when the type or letters of journals and books were manually mounted in trays called galleys for printing and review. However, despite technological transformations, its objective remains to allow the review of the manuscript by the editor and the author before the publication of the article. Here, the editorial production staff or the editor can ask the author about changes or amendments in the text, indicating marks so that the author knows what to review. The author, for his part, has the last opportunity to accept or reject the proposed changes, request minor corrections, and answer queries from the editorial production. At this stage only critical changes should be made, for example correcting errors in data and figures, not extensive revisions to the text. Editors usually give a short time (24 to 72 hours) for the author to return the revised proof. Some journals also have other complementary stages of quality control.

After the final review, DOI attribution can be made to the articles. Once this stage of editorial production is completed, the manuscript is about to become a published article and may be distributed in various formats (PDF, XML, ePub). Also, full texts and metadata can be harvested automatically or deposited in databases and indexes.

As an example, in figure 5 we represent the flowchart of the editorial process carried out for the journals in the Editorial Ciencias Médicas (ECIMED) of Cuba.

Figure 5. Flowchart of the editorial process of Editorial Ciencias Médicas (ECIMED), Cuba

Source: personal email communication with José Enrique Alfonso Manzanet, head of the Department of Medical Journals of ECIMED, March 9, 2021

As can be seen in the figure 5, ECIMED is also integrating the preprint repositories within the flowchart, in line with the strategies for the development of an open science. In this way, authors with their manuscripts approved in desk-review have the possibility of depositing their manuscripts in a preprint server, if they wish, while the peer review process occurs simultaneously. Along the same lines, the Revista Cubana de Información en Ciencias de la Salud (Cuban Journal of Information on Health Sciences), one of the journals published by ECIMED, indicates on its website that:

“Authors are allowed and recommended to disseminate their work on the Internet (e.g., in institutional repositories or on their website) before and during the submission process, which can lead to interesting exchanges and increase citations of the published work. (See The effect of open access). In this case, we request that the header of the manuscript indicate: “This is a preprint version of the article sent to the Revista Cubana de Información en Ciencias de la Salud http://rcics.sld.cu/” (Source: http://www.rcics.sld.cu/index.php/acimed/about/submissions )

Next, I will briefly refer to publication “models” and then to other important phases such as indexing in databases, dissemination, and journal impact evaluation.

Publication models

There are at least three models for publishing articles. In the traditional editorial production model, where journals publish several issues per year (each year considered a volume), the editors or the editorial board select and define, from among the approved manuscripts, how many and which ones will be part of a specific issue. Therefore, the issue is only published when all the manuscripts selected and grouped in blocks (issues of an edition) satisfactorily comply with all the stages mentioned above.

However, this way of working and publishing can bring unnecessary delays in the communication of scientific results, since accepted articles will have to wait to be published for as long as it takes to complete the issue or, even, some would have to wait to come out in a next issue (three months later or more, depending on the periodicity of the journal). That, because the package of articles selected to make up that particular issue is already complete (the maximum number of articles previously established per issue has been reached or the deadline for “closing” that issue has been reached).(41)

Seeking to increase the exposure time of articles and increase their visibility, some journals began to use a complementary model to the traditional one called Ahead of print/Online First Publication. In this model, the articles already approved are published in a digital version before the final composition of the issue and its eventual publication (and printing). Although, from the point of view of content, these articles are finalized, they are not integrated into an issue, so they do not have volume and issue identifiers or definitive page numbers. Therefore, when the articles are attributed to an issue, they will have to be redrawn to include the final data. The Ahead of print model primarily meets the needs of journals that still publish a print version and want to speed up the display of finished articles while the rest is finalized to make up the issue. A guide for Ahead of print publication can be consulted on the SciELO website.(42)

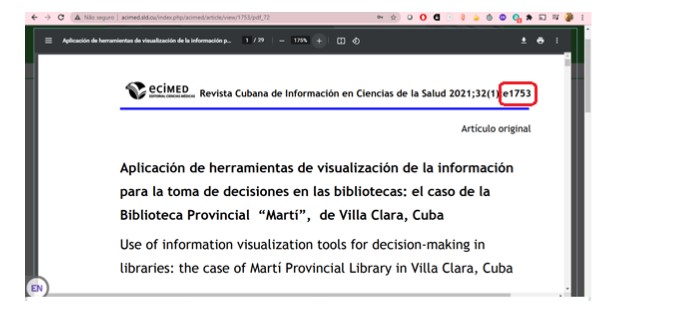

The third model, known as Continuous publication, has become very popular, especially among fully electronic and open access journals. Among its forerunners in scientific publication is the British Medical Journal (BMJ). In an editorial article announcing this change, editors argued that user behaviors on the web suggest that individual articles arouse even more interest than the journals in which they appear. (41) In this model, articles are published individually or in small batches, once they have passed satisfactorily through the stages of peer review, proofreading, and layout, that is, once the articles are already in their final form (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Publication process in a continuous publication model

Source: Adapted from SciELO(43)

In Continuous publication model, articles do not have the conventional pagination, but rather an electronic identifier (elocation-ID) (Figure 7). The numerical indicator can be constructed in various ways, for example, using the manuscript identification number in the electronic journal management system (43).

Figure 7. Example of using an e-location identification number for articles in continuous publication

Source: http://www.acimed.sld.cu/index.php/acimed/article/view/1753

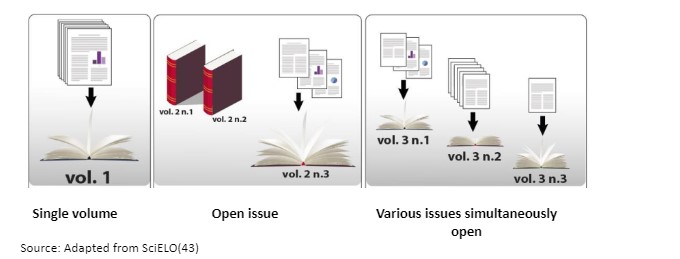

There are at least three variants for continuous publishing (43) (Figure 8):

- Publish articles in a continuous flow in a single volume per year

- Maintain the structure of several issues per year and publish articles in issues that remain open until the close of their periodicity

- Keep several issues open that are fed simultaneously

Figure 8. Variants of the continuous publication model

Source: Adapted from SciELO(43)

It is necessary to reinforce that the use of the Continuous Publication model aims to accelerate publication (and, therefore, the exposure and visibility of articles) and should not be used to correct or minimize publication timeliness problems.

With the publication of the issue or articles, whatever the model used, we must not end the editorial management. Other stages are very important for the scientific journal to fulfill the functions and expectations of readers, authors, their institutions, and funders.

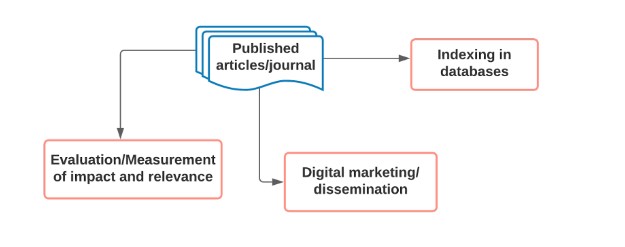

The stages shown below (Figure 9) are related to the expectation of increasing the visibility of the journal, its recognition and impact in a scientific community (and in the society as a whole) through digital marketing and science dissemination strategies, indexing in national and international indexes and databases, as well as the measurement of access, use, and visibility indicators, among others. I briefly comment on these stages below.

Figure 9. Stages of the editorial process: indexing, dissemination, and evaluating

Indexing in databases

Indexing in this context is the incorporation of metadata (author, title, keywords, etc.) that represent articles in indexes or databases, such as LILACS, DOAJ, SCOPUS, Redalyc, SciELO, Web of Science, among others. Each database has its specific objectives and criteria for the inclusion of journals and their articles. Some criteria are basic, such as having an ISSN (International Standard Serial Number), an established publication agenda and periodicities, copyright policies, and article-level metadata. Other additional requirements may include adjusting to the subject area of the database, the composition and professionalization of the editorial team, including information about the peer review process or even criteria related to citations received.

In the case of LILACS (Latin American Literature in Health Sciences), a reference and full-text database, whose mission is to provide access and visibility to the best scientific production in health sciences in the Latin American and Caribbean region, scientific merit is the main criterion for inclusion, reflected in attributes of the published research such as its originality, validity, and contribution to the subject area. However, journals must also meet other criteria such as including their full text in open access, preferably accompanied by a Creative Commons CC-BY license, as well as publishing more than 50% of original articles. To get to know other indexing criteria and characteristics of LILACS, I suggest consulting the document “Selection Criteria and Permanence of Journals” (2020) (37) and the lecture by Suga (44), in the context of the webinar “Best Practices in LILACS Editorial Processes 2020”.

Database indexing enhances the visibility, search, retrieval, use, and citation of articles and, therefore, the construction of a reputation that will also result in satisfying the expectations of the actors of the scientific communication system. A very important aspect is the quality of the metadata, which must be machine-readable.

There are two fundamental ways to incorporate metadata into a database:(45)

- Web Crawlers/Harvesters: Some databases index journal articles on their own through web crawlers, which are automated Internet programs that “crawl” websites to collect or “harvest” metadata. For crawlers to easily identify new content, publishers must apply metadata to articles and maintain a website structure that meets the index’s requirements.

- Metadata/content repository: Many indexes do not use web crawlers and instead require publishers to submit metadata (and even full text) in machine-readable formats. In this case, machine-readable metadata files (often XML) must be deposited in the database so that it can process the article information and know what to return in the search results.

For journals interested in indexing in LILACS there are also these two mechanisms for the incorporation of articles: an automatic harvest of the metadata of those journals that are also indexed in SciELO and the manual deposit of metadata in the database, which it is usually carried out by the librarians of the LILACS Network of Cooperating Centers.

However, LILACS is encouraging a more active participation of the editors themselves in this metadata deposit process, using the Lilacs-Express tool, which allows for the creation of a registry with basic metadata of published articles. As advantages of this “pre-cataloging”, articles are immediately published in the database, along with their full texts, which speeds up the visibility and accessibility of the articles. The librarians of the Network of Cooperating Centers subsequently enrich these records with additional metadata, including subject descriptors. For a more complete explanation of the operation of Lilacs-Express and its integration with the editorial processes, I suggest consulting the lectures by Suga and Paula (46) within the framework of the II Training Latin American and Caribbean Network of Information in Health Sciences-2020.

Scientific digital marketing and social media dissemination

Scientific digital marketing is based on traditional marketing theories and methodologies to create actions and services, allied to interactive communication resources, that allow for the promotion of journals, their articles, their authors, and reviewers, also establishing lasting relationships with the journal’s users. (47,48)The main channels used are blogs and social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, Instagram, among others.

In this sense, three issues are essential (48): building and maintaining an online presence, offering content appropriate to the selected environment, and establishing an active and proactive action. These aspects will also allow monitoring through metric indicators that will facilitate estimating attributes such as visibility, interaction, influence, and use, among others. To know recommendations, strategies and examples of the use of social networks to contribute to the dissemination of the contents of scientific journals, I suggest consulting the lectures by Cerqueira (49) and Flores (50) in the LILACS Best Editorial Practices webinar, 2019 and 2020 editions, respectively.

Measurement of visibility and relevance of published content

The evaluation of scientific journals has a history dating back to the 1930s, driven by the need for librarians to select the most relevant titles, in a context of proliferation of journals and articles. Indexing services are also beginning to adopt criteria to filter and select the highest quality titles. This is how bibliometric studies and subsequently the citation indexes and the impact factor indicator emerge, as a measure of the reputation of the journals based on the citations received. The implementation and extension of the policies and systems for evaluating the performance of researchers gave a definite boost to the evaluation of journals, and researchers start to be valued for their productivity and the reputation of the publication channel. It became necessary to define the quality criteria of the journals, and the lists, classifications, and measurement indicators proliferated. I have mentioned quality criteria in other parts of this chapter. A more complete analysis can be consulted in López-Cózar (51).

A self-assessment based on quality criteria and the application of metric indicators is also a best practice for editorial teams to align their trajectory to meet the expectations of the scientific community and society, always in accordance with their scope, mission, and vision. It is a comprehensive evaluation that Reis calls, in a lecture delivered at the “LILACS 2020 Best Practices in Editorial Processes” webinar (52), a proactive management model, where a multidimensional and proactive evaluation is carried out. In contrast, a reactive management would be focused solely on achieving an impact factor or making changes because the indexing databases so request. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation should consider criteria that allow critical judgment, for example, editorial policies, instructions to authors, the composition of the board of reviewers, the peer review model, and editorial production flows.

I also consider important the application of different indicators that allow a global vision of what we are publishing (or not publishing) and what are the impacts, beyond citations, that we are achieving in the scientific community and society in general. In addition to the traditional production and citation indicators, alternative indicators (altmetrics) are also currently added, which are applied to content shared through social media platforms (48). Traditional and alternative metric indicators, applied to scientific production published by a journal, allow, for example, to identify articles, topics, and types of articles with the greatest impact on the scientific community, by measuring the number of downloads, views, mentions in social networks or citations in databases.

Other aspects that could be analyzed from bibliometric and altmetric indicators are the circulation of articles by geographical regions, the thematic niches that can be best explored, and the characteristics at the individual or institutional author level of the published articles (for example, who are our authors? What institutions are they affiliated with? In what language do they write? What are the types of articles or sections with the most contributions?). These analyses would allow us to draw up editorial management strategies such as policy redefinition, improvement of editorial processes, marketing and dissemination strategies, selection of databases for indexing, among others.

In this chapter I gave an overview of best practices related to the editorial processes of a scientific journal, including a characterization of its participants and their functions. This topic is relevant due to the need for scientific journals published in Latin America and the Caribbean, even when preserving their non-commercial nature, supported by infrastructure and public funding, to achieve higher quality, visibility, recognition, and reputation as important channels for the dissemination of science, both for Latin American researchers and for those from other parts of the world.

In this way, the chapter begins by presenting the main expectations and motivations for the publication and consultation of scientific journals, continues with the characterization of the actors involved in the scientific and editorial management of the journal and their essential functions, with emphasis on the editor and librarian. At the center of the exposition are the stages of the editorial process, both those understood as scientific management (evaluation of the manuscript) and the stages of editorial production (proofreading, standardization, layout, among others). This part also presents the publication models that currently coexist, showing the relevance of continuous publication. The chapter ends by showing that after publication, other processes have great relevance for the quality and visibility of journals, such as indexing in databases, marketing and dissemination of content, and evaluation processes.

References

- Mabe M. Scholarly Communication: A Long View. New Review of Academic Librarianship. 2010;16(S1):132-44.

- Fuchs C, Sandoval M. The Diamond Model of Open Access Publishing: Why Policy Makers, Scholars, Universities, Libraries, Labour Unions and the Publishing World Need to Take Non-Commercial, Non-Profit Open Access Serious. tripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique [Internet]. 2013 [cited 13 December 2020];11(2):428-43. Available at: https://www.triple-c.at/index.php/tripleC/article/view/502

- Sánchez-Tarragó N. Ciência aberta e acesso aberto para o Sul: perspectivas críticas e desafios. In: Moreira L de A, Souza, Jacqueline Aparecida de, Tanus GF, editors. Informação na Sociedade Contemporânea. Florianópolis: Rocha Gráfica e Editora (Selo Nyota); 2020. Available at: https://bit.ly/3lklFk1

- Babini D. La comunicación científica en América Latina es abierta, colaborativa y no comercial. Desafíos para las revistas. Palabra Clave (La Plata) – Revistas de la FaHCE [Internet]. 2019 [cited 10 March 2021];8(2):e065. Available at: https://www.palabraclave.fahce.unlp.edu.ar/article/view/PCe065

- Alperin JP, Fischman G, editors. Hecho en Latinoamérica: acceso abierto, revistas académicas e innovaciones regionales. Buenos Aires: CLACSO; 2015. 122 p. Available at: http://biblioteca.clacso.edu.ar/clacso/se/20150722110704/HechoEnLatinoamerica.pdf

- Sánchez-Tarragó N. Flujo editorial. In: Buenas Prácticas Procesos Editoriales LILACS 2020 [Internet]. LILACS; 2020 [cited 10 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TMaiTdzArrE&list=PLfsV9tOIWTCczImNyFvpanJe3DA9fsKfw&index=4&t=2169s&ab_channel=RedBVS

- ISO 8:2019(en), Information and documentation — Presentation and identification of periodicals [Internet]. 2019 [cited 18 February 2021]. Available at: https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:8:ed-2:v1:en

- Jonhson R, Watkinson A, Mabe M. The STM Report: An overview of scientific and scholarly publishing [Internet]. The Hague: International Association of Scientific, Technical and Medical Publishers; 2018 [cited 16 February 2021]. Available at: https://www.stm-assoc.org/2018_10_04_STM_Report_2018.pdf

- Rego TC. Produtivismo, pesquisa e comunicação científica: entre o veneno e o remédio. Educ Pesqui [Internet]. June 2014 [cited 22 February 2021];40(2):325-46. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1517-97022014000200003&lng=pt&tlng=pt

- Barata RB. Desafios da editoração de revistas científicas brasileiras da área da saúde. Ciênc saúde coletiva [Internet]. March 2019 [cited 18 May 2020];24(3):929-39. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1413-81232019000300929&tlng=pt

- Declaración De San Francisco Sobre La Evaluación De La Investigación [Internet]. DORA. 2012 [cited 9 March 2021]. Available at: https://sfdora.org/read/read-the-declaration-espanol/

- Sandes-Guimarães LV de, Diniz EH. Gestão de periódicos científicos: estudo de casos em revistas da área de Administração. RAUSP [Internet]. 2014 [cited 11 May 2020];49(3):449-61. Disponible en: https://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?pid=S0080-21072014000300002&script=sci_abstract&tlng=pt

- Vázquez D. Calidad de las revistas científicas. In: Buenas Prácticas Proceso Editorial LILACS 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 27 February 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jb76MXePRI0&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_31IBhBz1Lt3RqGz6–sACt&index=2&t=2769s&ab_channel=RedBVS

- Trzesniak P. A Estrutura Editorial de um Periódico Científico. In: Sabadini AAZP, Sampaio MIC, Koller SH, editors. Publicar em psicologia: um enfoque para a revista científica [Internet]. Universidade de São Paulo. Instituto de Psicologia; 2009 [cited 27 February 2021]. p. 87-102. Available at: http://www.livrosabertos.sibi.usp.br/portaldelivrosUSP/catalog/book/16

- Trzeniak P. Definiendo y consolidando el alcance de la revista. In: Buenas Prácticas Editoriales LILACS 20 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 27 February 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=shJ8qprKPuQ&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_2-e_JGt1lkRUgU70ERrNDQ&index=2&ab_channel=RedBVS

- Paula A de SA de. Publicación de artículos: importancia y relevancia de la normalización en el flujo editorial. In 2019 [cited 27 February 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hPgS0wA1qm8&ab_channel=RedBVS

- Trzeniak P. Editorial team. In: Buenas Prácticas Proceso Editorial LILACS 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 27 February 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j_-Ab2ICBxU&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_31IBhBz1Lt3RqGz6–sACt&index=4&t=2400s&ab_channel=RedBVS

- Ali PA, Watson R. Peer review and the publication process. Nurs Open [Internet]. 2016 [cited 19 February 2021];3(4):193-202. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC5050543/

- Sánchez-Tarragó N, Díaz Álvarez YY. El sector editorial contemporáneo y las competencias profesionales. ACIMED [Internet]. 2005 [cited 28 February 2021];13(5):1-1. Available at: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1024-94352005000500008&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es

- Santillán-Aldana J, Mueller SPM, Santillán-Aldana J, Mueller SPM. The publishing service development by academic libraries. Perspectivas em Ciência da Informação [Internet]. 2016 [cited 28 February 2021];21(2):84-99. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1413-99362016000200084&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt

- Skinner K, Lippincott S, Speer J, Walters T. Library-as-Publisher: Capacity Building for the Library Publishing Subfield. Journal of Electronic Publishing [Internet]. 2014 [cited 1 March 2021];17(2). Available at: https://doi.org/10.3998/3336451.0017.207

- Gilmet A. Participación de bibliotecólogos en la edición científica en Uruguay. Informatio [Internet]. 2020 [cited 1 March 2021];25(2). Available at: https://informatio.fic.edu.uy/index.php/informatio/article/view/248

- Santa Anna J. O bibliotecário na editoração de periódicos científicos eletrônicos: possibilidades empreendedoras. Informatio Revista del Instituto de Información de la Facultad de Información y Comunicación [Internet]. 2019 [cited 1 March 2021];24(1):25-41. Available at: https://informatio.fic.edu.uy/index.php/informatio/article/view/218

- Díaz Álvarez YY, Sánchez-Tarragó N. Identificación de competencias en edición para los profesionales de la información. ACIMED [Internet]. 2006 [cited 1 March 2021];14(2):0-0. Available at: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1024-94352006000200002&lng=es&nrm=iso&tlng=es

- Maimone G, Tálamo M de F. A atuação do bibliotecário no processo de editoração de periódicos científicos. Revista ACB: Biblioteconomia em Santa Catarina. 2008;13(2):301-21.

- González JTG. Experiencias de bibliotecólogos que laboran en bibliotecas universitarias en los procesos editoriales de revistas académicas mexicanas. Biblios: Journal of Librarianship and Information Science [Internet]. 2019 [cited 1 March 2021];(75):1-15. Available at: https://biblios.pitt.edu/ojs/index.php/biblios/article/view/467

- Rozemblum C, Banzato G. La cooperación entre editores y bibliotecarios como estrategia institucional para la gestión de revistas científicas. Información, cultura y sociedad [Internet]. 2012 [cited 1 March 2021];(27):91-106. Available at: http://revistascientificas.filo.uba.ar/index.php/ICS/article/view/686

- Santana SA, Francelin MM. O bibliotecário e a editoração de periódicos científicos. RBBD, Rev Bras Bibl Doc [Internet]. 20 de agosto de 2016 [cited 16 May 2020];12(1):2-26. Available at: https://rbbd.febab.org.br/rbbd/article/view/543

- Jiménez-Hidalgo S, Giménez-Toledo E, Salvador-Bruna J. Los sistemas de gestión editorial como medio de mejora de la calidad y la visibilidad de las revistas científicas. El Profesional de la Informacion [Internet]. 2008 [cited 1 March 2021];17(3):281-91. Available at: https://revista.profesionaldelainformacion.com/index.php/EPI/article/view/epi.2008.may.04

- Massimo L, Codato A. Sobre a rejeição imediata de manuscritos sem pareceres externos [Internet]. SciELO em Perspectiva. 2016 [cited 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://blog.scielo.org/blog/2016/08/10/sobre-a-rejeicao-imediata-de-manuscritos-sem-pareceres-externos/

- Froese FJ, Bader K. Surviving the desk-review. Asian Bus Manage [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2 March 2021];18(1):1-5. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1057/s41291-019-00060-8

- Teixeira da Silva JA, Al-Khatib A, Katavić V, Bornemann-Cimenti H. Establishing Sensible and Practical Guidelines for Desk Rejections. Sci Eng Ethics. August 2018;24(4):1347-65. Available at:

- Nassi-Calò L. Ética en la publicación científica. En: Buenas Prácticas Proceso Editorial LILACS 2019 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8tOWBlf0qVU&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_31IBhBz1Lt3RqGz6–sACt&index=5&ab_channel=RedBVS

- COPE. Core practices [Internet]. 2017 [cited 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://publicationethics.org/core-practices

- ICMJE. Responsibilities in the Submission and Peer-Review Process [Internet]. [cited 2 March 2021]. Available at: http://www.icmje.org/recommendations/browse/roles-and-responsibilities/responsibilities-in-the-submission-and-peer-peview-process.html

- Spinak E. Sobre as vinte e duas definições de revisão por pares aberta… e mais [Internet]. SciELO em Perspectiva. 2018 [cited 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://blog.scielo.org/blog/2018/02/28/sobre-as-vinte-e-duas-definicoes-de-revisao-por-pares-aberta-e-mais/

- LILACS. LILACS – Criterios de Selección y Permanencia de Revistas (2020) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 9 March 2021]. Available at: https://lilacs.bvsalud.org/es/revistas-lilacs/lilacs-criterios-de-seleccion-y-permanencia-de-revistas-2020/

- Squazzoni F. Avaliação por pares não é apenas controle de qualidade, é parte integrante da infraestrutura social da pesquisa [Internet]. SciELO em Perspectiva. 2020 [cited 2 March 2021]. Available at: https://blog.scielo.org/blog/2020/01/15/avaliacao-por-pares-nao-e-apenas-controle-de-qualidade/

- Rodríguez EG. La revisión editorial por pares: rechazo del manuscrito, deficiencias del proceso de revisión, sistemas para su gestión y uso como indicador científico. Revista Cubana de Información en Ciencias de la Salud [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2 March 2021];24(3). Available at: http://acimed.sld.cu/index.php/acimed/article/view/420

- Rodríguez EG. La revisión editorial por pares: roles y procesos. Revista Cubana de Información en Ciencias de la Salud [Internet]. 2013 [cited 2 March 2021];24(2). Available at: http://acimed.sld.cu/index.php/acimed/article/view/410

- Sánchez-Tarragó N. La Revista Cubana de Información en Ciencias de la Salud adopta el modelo de publicación continua. Revista Cubana de Información en Ciencias de la Salud [Internet]. 2017;28(2):1-3. Available at: http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S2307-21132017000200006

- SciELO. Guia para a publicação avançada de artigos Ahead of Print (AOP) no SciELO [Internet]. 2019. Available at: https://wp.scielo.org/wp-content/uploads/guia_AOP.pdf

- SciELO. Guia para Publicação Contínua de artigos em periódicos indexados no SciELO [Internet]. 2019 [cited 9 March 2021]. Available at: https://wp.scielo.org/wp-content/uploads/guia_pc.pdf

- Suga SMY. Por que indexar em LILACS? In: Buenas Prácticas Procesos Editoriales LILACS 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 1 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TTL_NuMMDjw&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_2-e_JGt1lkRUgU70ERrNDQ&ab_channel=RedBVS

- Padula D. Indexación de revistas: estándares básicos y por qué son importantes [Internet]. SciELO en Perspectiva. 2019 [cited 1 March 2021]. Available at: https://blog.scielo.org/es/2019/08/28/indexacion-de-revistas-estandares-basicos-y-por-que-son-importantes-publicado-originalmente-en-el-blog-lse-impact-of-social-sciences-en-agosto-2019/

- Suga SMY, Paula A de SA de. Creación de nuevos registros LILACS-Express en el FI-Admin. In: II Capacitación Red Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Información en Ciencias de la Salud (May 2020) [Internet]. 2020 [cited 9 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7J0WkN3-K8U&ab_channel=RedBVS

- Bomfá C, Freitas M, Silva L, Bornia A. Marketing Científico Electrônico: um novo conceito voltado para periódicos electrônicos. Revista Estudos em Comunicação [Internet]. 2009 [cited 9 March 2021]; Available at: http://www.ec.ubi.pt

- Araújo RF de. Marketing científico digital e métricas alternativas para periódicos: da visibilidade ao engajamento. Perspectivas em Ciência da Informação [Internet]. 2015 [cited 9 March 2021];20(3):67-84. Available at: http://www.scielo.br/scielo.php?script=sci_abstract&pid=S1413-99362015000300067&lng=en&nrm=iso&tlng=pt

- Cerqueira R. Divulgación científica. In: Buenas Prácticas Procesos Editoriales LILACS 2020 [Internet]. 2019 [cited 1 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HETa4BEfLX8&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_31IBhBz1Lt3RqGz6–sACt&index=9&ab_channel=RedBVS

- Flores NM. ¿Qué contenido debo destacar? In: Buenas Prácticas Procesos Editoriales LILACS 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 1 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=o2jXSlgSw3M&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_2-e_JGt1lkRUgU70ERrNDQ&index=5&ab_channel=RedBVS

- López-Cózar ED. Evaluar revistas científicas: un afán con mucho presente y pasado y futuro incierto. In: Abadal E, editor. Revistas científicas: Situación actual y retos del futuro. Barcelona: Universitat de Barcelona; 2017. p. 73-103. Available at: http://eprints.rclis.org/32132/

- Reis JG. Conócete a ti mismo. In: Buenas Prácticas Editoriales LILACS 2020 [Internet]. 2020 [cited 1 March 2021]. Available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Apl8AxMAP7M&list=PLZkQ-JIKvi_2-e_JGt1lkRUgU70ERrNDQ&index=8&ab_channel=RedBVS

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.