Dr. Damián Vázquez

https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3551-9251

Editor-in-Chief, Pan American Journal of Public Health

Pan American Health Organization

Introduction

As of this writing, the world has been immersed in the coronavirus pandemic for more than a year and a half, and it has provided countless examples of good (and bad) scientific communication. The quality of scientific communication depends on multiple factors. Content is certainly very important, but there are other factors equally relevant to communicating science effectively. Among them can be mentioned the correct use of international conventions and an adequate scientific language, everything that leads to communicating with precision and clarity.

The transmission of scientific knowledge is essential for the advancement of science. New scientific discoveries are based on previous knowledge, and from there, the importance of the latter being published and accessible to the entire scientific community. In this field of scientific communication, specialized knowledge has traditionally been disseminated through different media, such as conferences, books, seminars, and scientific articles.

Scientific articles are probably one of the most dynamic vehicles for transmitting new scientific evidence, since they can reach the scientific community shortly after an investigation is completed. The pandemic illustrates this dynamism: a simple search of the PubMed database of the United States National Library of Medicine turns up more than 140,000 articles on the disease caused by the coronavirus, COVID-19.

The guide to which this chapter belongs is practical, and therefore these guidelines are aimed at providing practical advice for writing articles and other scientific texts. It is not intended to be a detailed and exhaustive academic resource, but rather to emphasize certain aspects that contribute to making the resulting text technically sound. Scientific texts have a specialized content and contain a particular language, structure, and sections; these different aspects will be dealt with separately in order to simplify the presentation. The information presented may be useful for authors, researchers, editors, health professionals in general, and professionals who need to write or review scientific texts. Since the conventions on which scientific articles and language are based are international, the information provided in this chapter is generally applicable to many scientific texts, regardless of the language in which they are written.

Scientific language

Although each branch of science may have specific terminology and conventions, the language of science in general has characteristics that differentiate it from the language used in other fields. Since the purpose of a scientific text is to convey technical information, it must be clear, concise, and precise so that readers understand the key concepts without ambiguity. The readers of a scientific text can be diverse (e.g., researchers, specialized professionals, the general population) depending on the type of text, and the writer must keep the main audience in mind to adjust the content’s level of complexity. A text that is too complex for a general audience, and one that is too simple for a specialized audience are equally unsuitable.

To convey information unequivocally, scientific language uses internationally accepted conventions, which allow professionals from different parts of the world to exchange scientific knowledge. Below are some of these conventions.

The International System of Units: numbers and symbols

It might be thought that the writing of numbers does not offer difficulties in any language and that numbers cannot give rise to mistakes, but a practical example shows that this is not the case: in many Spanish-speaking countries the figure 15,345 implies fifteen thousand three hundred and forty-five units. In others, on the other hand, it is only fifteen units and three hundred and forty-five hundredths. This conceptual difference — and the potential for misunderstandings it entails — extends even further to English-speaking countries, where the comma is often used to separate thousands.

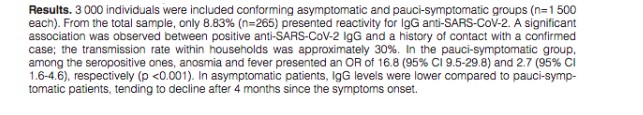

To avoid this ambiguity and facilitate communication between scientists, the International System (SI) recommends separating thousands with a space and avoiding the use of a comma or period. In a scientific text, the figure in the example should be written “15 345”, which denotes fifteen thousand three hundred and forty-five units. If that figure had decimals, the SI allows adding them after a comma or decimal point, depending on the preference of the scientific journal or the country: 15 345,22 is equally correct as 15 345.22 (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Proper writing of figures in a scientific article according to the International System of Units. Note the use of a space to separate the thousands.

Note that, with either of the two iterations, it is clear which are the integers and which are the decimals, regardless of the common use in a country and a language.

The SI also addresses the correct writing of units. These must be derived from the metric system, even when different units (e.g., yard, ounce, or inch) are used daily in a given country. In a scientific text, it is essential to use the units recognized by the SI and their symbols (e.g., meter and m, kilogram and kg, etc.). It is important to remember that the symbols, with a few exceptions, are written with a lowercase initial (kg and not Kg), are never followed by a period (kg and not kg.), and are not plural (1 m and 5 m mean 1 meter and 5 meters, respectively).

The taxonomy of living beings

As aforementioned, scientific texts must be precise, and when a living being is mentioned, it must be clear to which genus and species they refer. Again, this precision goes beyond the country and the language in which it is written and is based on an international standard that is known generically as the taxonomy of living beings. Although it comprises different hierarchies (phyla, classes, orders, families, genera, and species), for practical purposes we will refer here to the last two since they are the most commonly used in general scientific texts.

According to this nomenclature, the genus and species that identify a living being are written in Latin in any language. The genus must be capitalized and the species with a lowercase initial. Both must be written in a different typeface than the surrounding text, which usually means that they must be written in italics. Some examples of this nomenclature are Canis familiaris (common name in English, dog), Staphylococcus aureus (common name in English, staph), and Chlamydia (common name in English, chlamydia).

In a scientific text, incidentally, non-Latin common names can also be used, but their use must be clear and alternating between the taxonomic name and the common name without a technical basis must be avoided. Likewise, after entering the complete taxonomic name (genus and species) in a text, in the following iterations it is accepted practice to abbreviate the genus with its initial (e.g., S. aureus), always keeping the italics, if appropriate.

Finally, since taxonomic names are proper names (such as Liliana or Manuel) they should not be preceded by an article, that is, it should be written “Staphylococcus aureus is a resistant bacterium”, but not “The Staphylococcus aureus is a resistant bacterium”. On the contrary, the common name in English is a noun, and generally must be preceded by the definite article: “The dog is brown”. In the previous examples, no article before the taxonomic name is correct in written scientific language, but we note that spoken language is more relaxed, and it is not uncommon to hear the use of the article.

International Nonproprietary Name of drugs

Often, in a scientific text it is necessary to write the name of a drug, or of a drug marketed under a registered trademark (a medication).

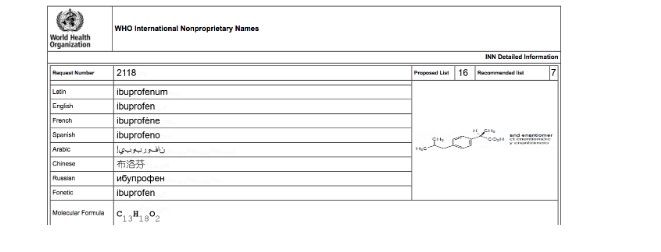

Drug names —generic names— must be written according to the so-called International Nonproprietary Name (INN), a nomenclature maintained by the World Health Organization.

Similar to what happens with the names of living beings, drug names are common nouns, and therefore must be written with a lowercase initial and, in some cases, may be preceded by an article: “A good anti-inflammatory drug is ibuprofen.” Medication names, on the other hand, are brands, and as such are proper nouns and must be written with a capital letter and without an article, even though in spoken language it is common to use the latter: “A good anti-inflammatory drug is Advil.” The use of the trademark symbol next to the name (®, TM, MR) is optional, since the initial capital letter already denotes that the name is a trademark (Figure 2).

Figure 2. International Nonproprietary Name of Ibuprofen. Note the first lowercase letter.

Since scientific texts must be devoid of commercial connotations, the use of the name of a drug should always be preferred over that of the medication, unless the mention of the commercial name is essential. Furthermore, the same drug could be marketed in different countries under different brand names, and therefore it is always advisable to write the name of the drug and not the brand.

The International Classification of Diseases

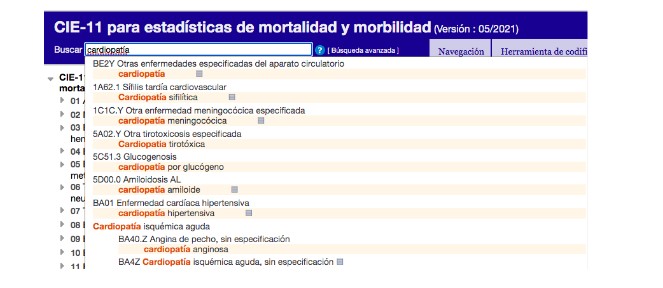

Diseases also have precise names, and these are included in the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), a nomenclature compiled and maintained by the World Health Organization. The names of diseases are common nouns, and as such must be written with a lower case initial: “Severe dehydration is one symptom of cholera”. For greater precision, if the text requires it, it is also possible to mention the code that the ICD assigns to each disease (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Names and codes of diseases in the ICD-11.

Other aspects to consider when writing scientific texts

The aforementioned aspects relate to normative systems that should be consulted as necessary when writing a scientific text so that figures, units, living beings, drugs, and diseases are written accurately and without ambiguity. As previously mentioned, the main objective of scientific texts is to convey technical information clearly and precisely. These characteristics differentiate this literary genre from others, such as the novel or poetry, and when writing a scientific text other aspects must also be considered. Some of them are mentioned below.

Internal coherence. The text must always refer to the same concept in the same way. For example, a text where ‘Staphylococcus aureus‘ and ‘staph’ are used alternately for no technical reason, or ‘erythrocyte’ and ‘red blood cell’ used interchangeably, sometimes confuses the less specialized reader and makes the reading more tiring. For clarity and precision, and unlike the general literature, in scientific texts the use of synonyms should be very measured or avoided altogether, and their use should have a technical justification and be duly clarified.

Abbreviations and acronyms. While it may be tempting to use abbreviations “to save space,” the writer should be aware that some acronyms are highly specialized or restricted to a scientific field, place, or institution, and may not be understood by all readers. As a general rule, it is advisable to make a restricted use of acronyms, use them if truly necessary (that is, if they replace very long expressions that are repeated with great frequency) and always clarify them when they are introduced in the text for the first time. A text with an excess of acronyms is difficult to follow, particularly if they are little known.

Acronyms should preferably be used in one’s own language, but in some cases a given concept (and its acronym) become known in a language other than one’s own (typically, in English). For example, in Spanish the acronym VIH for the human immunodeficiency virus is widely spread, and it is not necessary to use the English acronym, HIV. On the other hand, the acronym for the United States Federal Bureau of Investigation, FBI, has been imposed in English in all languages and an acronym “adapted” to another language would generate surprise in the reader, if not confusion.

Foreign words. Scientific language evolves at the rate of scientific discoveries. Since many of these today are initially published in English, it is not uncommon for many languages to have widespread use of the English term, or anglicism. The decision of whether or not to use a foreign word when writing in one’s own language can be affected by several factors, some of them even personal, but some practical suggestions can be offered.

When there is a clear and unequivocal word in the language itself, it does not seem necessary to use a foreign word. For example, ‘cribado’ (or ‘tamizaje’, or ‘detección sistemática’; all ‘screening’, or similar, in Spanish) makes it unnecessary to use ‘screening’, and the same could be said of ‘aleatorizar’ versus the anglicism ‘randomizar’ (from ‘randomize’). In other cases, however, there does not seem to be a universally accepted word in the language itself, and it may be convenient to keep the word in English or an adapted variant. A current example may be ‘COVID’. The usage has imposed the acronym ‘COVID’ in practically all languages, and it would be confusing to introduce a translation such as ‘ENCOV’ to refer to ‘enfermedad por coronavirus’ (coronavirus disease). Box 1 presents a case study on this English acronym and its use in other languages and analyzes language as a living and changing collective construction.

| Box 1. The use and the norm: COVID, el or la COVID, and how ‘SIDA’ (‘AIDS’) became ‘sida’

The academic norm on the correct writing in a language usually recommends avoiding the use of foreign words, be they words or acronyms. Sometimes, however, the use of a foreign word becomes frequent and ends up imposing itself. This seems to be the case with the English acronym COVID (COronaVIrus Disease), which the pandemic has imposed in practically all languages. The use of COVID in languages other than English is so widespread that it is difficult to imagine that at some point the coronavirus disease will be known in Spanish by an acronym such as EC or ENCOV. The collective decision of speakers to use COVID in languages other than English is not objectionable and, in fact, using any of the aforementioned Spanish acronyms could lead to confusion. Something similar happens with the use of articles. According to the academic norm, in Spanish the article that precedes an abbreviation or acronym must agree with the main noun contained in the acronym (e.g., it must be written ‘el’ HIV, since it is el virus de la inmunodeficiencia humana (the human immunodeficiency virus)). But language is a collective and living construction in the hands of its speakers, and at the time of writing this guide, it seems as common to see ‘la COVID’ (for ‘la enfermedad’ or ‘the disease’, the central noun of the acronym) written as ‘el COVID’ (which does not agree with ‘disease’, and whose origin may be due to the fact that the disease is assimilated to ‘el virus’, ‘the virus’, that causes it). Time will tell if either of the two uses ends up more widespread or if both coexist, but neither of the two seems objectionable. Suffice it to say only that the use of one or the other should be uniform throughout the text. Finally, the generalized use turns many acronyms into common nouns, so that they begin to be written in lower case and according to the general rules of spelling (e.g., the acronym ‘SIDA’, or AIDS, evolved to the noun ‘sida’, and LASER, light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation, to ‘laser’). ‘COVID’ could follow the same path and end up being written as ‘covid’. |

Jargon. It includes terminology used by a small group of people or in a specific place, but which is difficult to understand outside that group or place of origin. As we have discussed, scientific language should be as broad a vehicle for the dissemination of information as possible and, in this context, jargon should be avoided. It is necessary to differentiate it, however, from the cultured and generalized use of certain terminology in an academic field, even when it is different from the modality used by the general population.

Figures and tables. It is often convenient to include figures or tables to present the information in a clearer and more orderly way. Avoid repeating the same information in the text, where it is enough to only mention the most important thing that the figure or table shows. These elements must be clearly identified with a number and cited in the appropriate place in the text. All tables and figures must have a clear and descriptive title.

The title. A technical or scientific document will likely include a title, and this item sometimes does not get the attention it deserves. The title is the reader’s first contact with the text and is often used to index that content in bibliographic databases. Thus, it must be clear and informative, that is, contain the necessary information without being too long (probably less than 12 words), and avoid anything that “takes up space” without providing information. In titles, it is also advisable to avoid including acronyms (except for universal ones).

Scientific articles

Scientific articles are a particular type of scientific text, and although detailed analysis is beyond the scope of this guide, some general tips for improving scientific article writing will be presented here.

Instructions for authors

A scientific article, by definition, will be published in a scientific journal. Most journals have a section on their website with instructions detailing the maximum acceptable length, the format of the references, the types of articles considered, and other information that will help to prepare the manuscript.

The different types of articles

Some of them are practically universal and common to many journals (e.g., original research articles or systematic reviews in biomedical journals). Each journal, however, may consider particular types of articles, such as book reviews, letters to the editor, comments, etc. Knowing what type of article you want to write and its characteristics, and which ones the chosen journal accepts, are key aspects.

The structure of scientific articles

The structure largely depends on the type of article. The classic “IMRD” structure (Introduction, Methods, Results, and Discussion) is usually applied to original research articles, although it may also be useful to use it in other types of articles. These sections can be considered as “drawers”, each of which must contain only what is pertinent in order to guarantee an orderly presentation of the information.

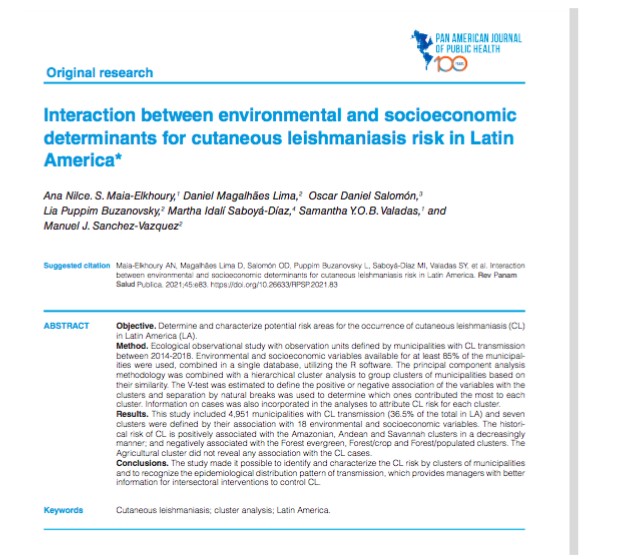

The Introduction should present the topic, the conceptual framework and the foundations of the study being presented, and the specific objectives of the article. The Methods (sometimes called Materials and Methods) should explain “what, when, and how” the study was conducted, including information related to study design, reagents, drugs, study population, and statistical treatment of the data. If the article describes research with human beings, the Methods must also mention the approval of the protocol by an ethics committee, the informed consent, and the measures taken to anonymize the data and treat it confidentially. In the Results, the specific findings of the study should be described and, where appropriate, these can be presented using tables and figures. Finally, in the Discussion, the results should be interpreted and contrasted with those found in other studies. The final part should include the limitations of the study and its main conclusions (Figure 4).

Figure 4. First page of a scientific article with its title, bibliographic citation, abstract, and keywords.

The authors and collaborators

Although it may seem obvious, it is advisable to define from the beginning who the authors will be based on their specific merit with respect to the text or scientific study in question. International scientific journals follow precise authorship criteria that are important to know, and those who do not have sufficient merit to be considered authors can be included in the acknowledgment paragraph. We refer the reader to the International Committee of Medical Journal Editors reference to know in detail the authorship criteria used by most established scientific journals.

The title

As previously mentioned, the title represents the reader’s first contact with the text, and in a short text such as a scientific article, it acquires maximum importance. Thus, it must be clear, precise, concise (no more than 12 words or so), explicit, and informative. Certain frequent expressions in the titles only take up space without giving more information (… and literature review, Study on…, About…, Current study…, etc.).

The abstract

Scientific articles and other scientific texts usually include an abstract. Together with the title, it provides the reader with the first approximation to the content of that text, and therefore should be written with the utmost dedication. It must be informative, clear, and precise and, of course, fully reflect the content of the full text. If the abstract belongs to a scientific article, it is important to remember that some bibliographic databases only include the title and abstract (but not the full text), and this is an additional reason to pay close attention to these two elements. Whether a reader becomes interested in, reads, and potentially cites the entire article will depend on them.

In both the title and the abstract, acronyms (except universally known ones), jargon, and localisms should be avoided. In order to verify that the title and abstract are clear and understandable, a resource accessible to any author is to ask for the opinion of a colleague.

Keywords

In scientific texts, keywords are those specific terms that describe a given topic and are taken from specific thesauri (terminological lists). Of these, the two most widely used are MeSH (Medical Subject Headings, which contains terms in English) and DeCS (Descriptors of Health Sciences, which contains terms in English, Portuguese, and Spanish). Therefore, authors must exclusively use terms taken from the thesaurus recommended by the journal. Links to these two resources are provided in the bibliography section.

Bibliographic references

The bibliographic references give scientific support to the manuscript and must be current (preferably from the last five years), relevant, and pertinent. When it comes to a scientific article, the journals accept a maximum number of references, which is important to know in advance. There are different formats for writing references (e.g., Vancouver, Harvard, etc.) and each journal has its own preference. Some computer programs, known as bibliographic reference managers, are very useful for managing their order and format (e.g., EndNote, Zotero, Mendeley, etc.). It is advisable to cite primary references rather than secondary sources (e.g., an original article rather than a systematic review citing that original article).

Final recommendations

Scientific writing, including writing articles, guides, or technical reports, is a complex skill that is acquired through practice. As mentioned, it implies knowledge of several different aspects, but that ultimately converge in the scientific text. It is advisable to start with simple texts and, if possible, rely on a more experienced author. Submitting your own production to review by an experienced professional and receiving constructive criticism should not be discouraging, but rather encouragement on the way to acquiring writing skills. As a complement to this chapter, it is highly recommended to read the selected bibliography at the end. Among the resources, the Introductory Course on Scientific Communication in Health Sciences, available free of charge in Spanish and Portuguese, may be particularly useful, a natural and appropriate complement to this guide.

We encourage readers to spend time learning scientific writing. We do not doubt that it will represent an effective investment in terms of academic knowledge, professional development, and promotion of science in a broad sense, which in turn will result in a better quality of life for all populations in our region.

Recommended bibliography and resources

General resources

Introductory Course on Scientific Communication in Health Sciences. Online self-learning course, without tutoring and with certificate of participation. It addresses topics such as scientific writing, the publication of scientific articles, authorship, and ethics in publication, among others. Eminently practical in nature, it includes support materials, a bibliography, and exercises. In Spanish and Portuguese). Course program.

BIREME (The Latin American and Caribbean Center on Health Sciences Information). Specialized center of the Pan American Health Organization dedicated to promoting technical cooperation in scientific information on health. https://www.paho.org/en/bireme

Virtual Health Library. Network of networks and operational platform of the Pan American Health Organization for the management of health information and knowledge in Latin America and the Caribbean. https://bvsalud.org/en/

LILACS, Latin American and Caribbean Literature in Health Sciences. Scientific publications from 26 countries, including clinical studies, reviews, guides, technical reports, and government publications. https://lilacs.bvsalud.org/en/

LILACS virtual sessions (2019). Collection of nine webinars on best practices in editorial processes developed by experts. http://red.bvsalud.org/lilacs/es/sesiones-buenas-practicas-edicion-revistas-cientificas-lilacs-2019/

LILACS virtual sessions (2020). Collection of webinars on best practices in editorial processes developed by experts. https://lilacs.bvsalud.org/es/buenas-practicas-en-los-procesos-editoriales-de-revistas-cientificas-para-lilacs-2020

Institutional Repository of Information Sharing. Institutional repository of the Pan American Health Organization that gathers and makes available free of charge all the scientific-technical publications of the Organization. https://iris.paho.org/

Pan American Journal of Public Health. Open access scientific journal in English, Spanish, and Portuguese. Free for authors and readers. https://www.paho.org/journal/en

Scientific language

Mednet. Collaborative platform maintained by the World Health Organization that presents the official generic names of drugs (International Common Denomination) in English, Spanish, French, Chinese, and Russian, as well as biochemical information. http://mednet.who.int/inn

International Classification of Diseases, 11th revision (CIE-11). Disease nomenclature and coding tool. Washington, D.C.: Pan American Health Organization; 2021. https://icd.who.int/en

International System of Units. International Office of Weights and Measures. Symbols and international units required in scientific writing in any language. https://www.bipm.org/en/measurement-units

Royal National Academy of Medicine. Dictionary of Medical Terms. Madrid: Editorial Médica Panamericana; 2012. Print and electronic medical sciences dictionary.

Dicciomed. Medical-biological, historical, and etymological dictionary. Maintained by the Universidad de Salamanca in Spain. https://dicciomed.usal.es/

Cosnautas. Website with resources for writing and translation in biomedicine and health sciences. Some resources are free, but require registration. https://www.cosnautas.com/en

Writing scientific articles

Descriptors in Health Sciences (DeCS). Terminological list of keywords in Spanish, Portuguese, and English maintained by BIREME/PAHO/WHO. https://decs.bvsalud.org/en/

Medical Subject Headings (MeSH). Terminological list of keywords in English, maintained by the United States National Library of Medicine. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/mesh/meshhome.html

International Committee of Medical Journal Editors. Useful information on authorship, bibliographic references, conflicts of interest, copyright, etc. http://www.icmje.org/

Day R and Gastel B. How to write and publish a scientific paper. 8th edition; 2016. A practical and readable book on writing scientific articles; in English.

United States National Library of Medicine. Examples of how to cite different types of resources in a scientific article. https://www.nlm.nih.gov/bsd/uniform_requirements.html

Clarivate Analytics. EndNote. Bibliographic references manager. https://endnote.com/

Corporation for Digital Scholarship. Zotero. Bibliographic references manager. https://www.zotero.org/

Mendeley Corp. Mendeley. Bibliographic references manager. https://www.mendeley.com/

Equator Network. International initiative that promotes the use of guidelines to publish research results. https://www.equator-network.org/

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.